Lessons for Life

Strong work ethic, treating everyone the same, and moving forward

By Wendy Reeves, Contributing Writer

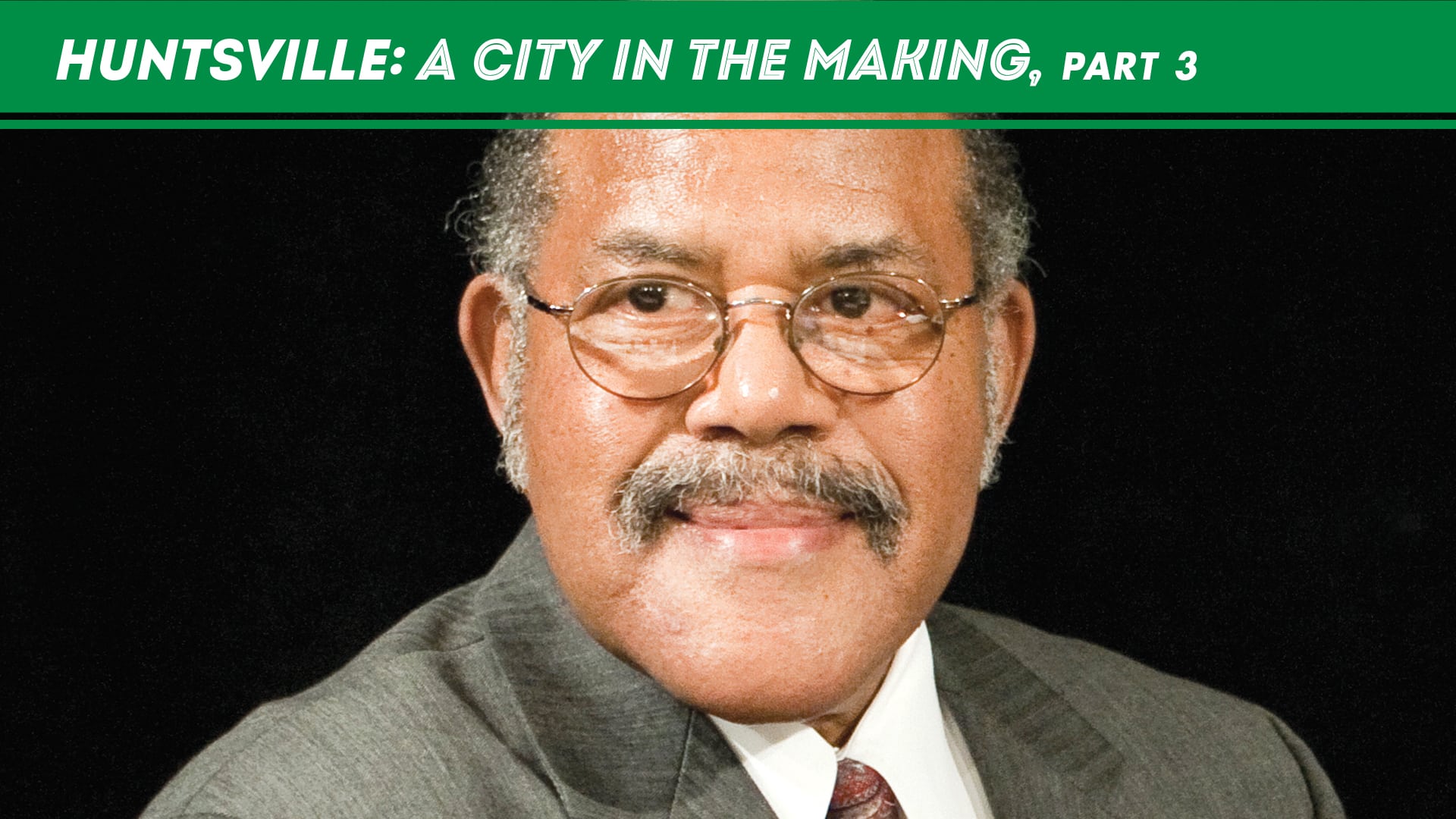

Hundley Batts, Sr.

From farming community, to the Rocket City and on to a research and development mecca, Hundley Batts, Sr., has been part of it all. He continues to play an integral role in Huntsville’s development as it continues on track to become the state’s largest city in just a few years.

Batts, 76, is a Huntsville businessman and longtime member and current Chair of Huntsville’s Industrial Development Board. He is also one of five diverse and influential leaders the Huntsville/Madison County Chamber is featuring in a special series of articles throughout 2020 called, “Huntsville: A City in the Making”. Others include W.F. Sanders, Jr., Julian Butler, Loretta Spencer, and Charles Younger.

Entrepreneurship is in his family’s DNA. When he was a young boy, Batts’ father ran a service station downtown where WHNT News 19 is located today, at the corner of Church Street and Holmes Avenue.

“He had a service station there, and as a little kid, I had me a Texaco star when I was in the third or fourth grade,” Batts recalled. “I had to come to work every day and pump gas, and I just enjoyed it to be honest with you because I had my own Texaco star (on his shirt), and after selling so many gallons, he would give me a little tip.”

That inspired the young Hundley to fill up the tanks of everybody who stopped if they could afford it.

His father instilled a strong work ethic in him from an early age. If he wasn’t washing or parking cars, he was cleaning up scrap iron and other debris at the shop. He took the payments to the liquor store for his father’s beverage house, and learned the ins and outs of how to help others plan a party.

Then, when he was old enough, Batts delivered newspapers. That’s how he first got started in the business world. Today, Batts owns radio stations and an insurance company.

“I don’t do anything illegal, immoral, or unprofitable,” Batts said.

That was also instilled in him by his father. In the early 1980s, Batts bought WEUP, the first black-owned radio station in Alabama.

“The capital came from my insurance business,” he said, adding he thinks he was the first black insurance agent to work for a nonblack insurance company in the 1960s.

Batts has always been a trailblazer because of the mentors he had while growing up. But he also remembers what it was like to live in Huntsville and be an African-American man during the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Like much of Huntsville’s history, even the civil rights movement here didn’t follow the trends of others places in the South.

“We were raised being asked not to do anything that was illegal, immoral or unprofitable, and our parents would not allow us to do things like sit-ins,” Batts said. “My Daddy would kill me if I violated” those rules.

He remembers one day during those tumultuous times when he went by himself to the bus station to get something to eat. A man told him he’d better go home or his father would find out he was there. At the time, he remembers thinking whatever was going on had nothing to do with him, but he went home.

“Daddy was strict on where we could go and what we did,” Batts said. “We could not be the city clown. He wouldn’t put up with it. So, from then on I went with Daddy for sit-ins when he ate at the bus station, and I didn’t get in trouble.”

Charles Younger, who was city attorney at the time, also recalls a tense time of racial relations, and how black and white community leaders worked together to get through it.

“Our community was dedicated to making the change to integration peacefully,” Younger said. “We had outside support people here … and we were very concerned about white militant groups – we even had the KKK applying for permits. We gave them permits; we did have a lot of marches, and we had sit-ins that were started.”

Younger said when leaders were notified about sit-ins, he went to every cafe management person and asked if they were going to serve everyone or ask them to leave. Everybody had different answers, but in the end, the events went as smoothly as possible.

“Our position was to keep the peace and protect everyone, to treat everyone the same,” Younger said. “We told our police officers they had to treat everybody alike. We were different from other communities where the police were anti-integration.”

Efforts to create sensational headlines in Huntsville were thwarted by community leaders, and when Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. arrived to make a speech at Oakwood College, he was given a police escort, Younger said.

And Batts remembers that, while the civil rights movement touched Huntsville, he’s always felt like it’s been a respectful place for all citizens. He said he’s always felt like a valued member of the community.

What he remembers most about his upbringing is “if you were a nice and respectful kid, you could get anything out of Huntsville. The Chamber even let me be a member of the Chamber of Commerce. This was just the normal way we operated, looking back at it.”

Batts went on to become the first African-American Board Chair of the Huntsville/Madison County Chamber, and he has served as Chair of the Industrial Development Board since 2015.

Through all he’s seen over the years, Batts said he believes Huntsville has hit its stride and is handling the rapid growth right now “better” than when the city started its expansion in the ’60s. He’s looking forward to seeing what the future holds.

This article appears in the June 2020 issue of Initiatives magazine, a publication of the Huntsville/Madison County Chamber.