Marking the Places where Huntsville Women Made History

By Donna Castellano

On the centennial anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the Historic Huntsville Foundation, the Twickenham Town Chapter of the DAR, and the Councill High School Alumni Association are creating a lasting tribute to Huntsville’s pantheon of suffrage heroes through four historic markers that recognize the Black and white Huntsville women whose fight for equal suffrage shaped the future of our nation. These markers will ensure that the stories of the leaders of the Huntsville Equal Suffrage Association (HESA) and the six Black Madison County women who successfully registered to vote in 1920 are permanently inscribed in the Huntsville landscape.

Huntsville’s suffrage movement began in 1895, when Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt spoke to an overflow crowd in Huntsville’s City Hall. After Anthony spoke, Milton Humes stepped forward and declared the creation of HESA. Many of the city’s most prominent men and women lined up to join. Knowing their attendance would violate Huntsville’s color line, no Black men or women attended the meeting. But Black women clearly understood the importance of women’s suffrage and how voting rights could benefit themselves and their community.

The white women who led HESA were philanthropic and worked for the betterment of their community. They founded the City Infirmary, the forerunner of Huntsville Hospital. They supported the public library and funded literacy campaigns. They wanted better schools, health and sanitation reforms, and workplace reforms to keep children from textile mills and coal mines. Their prejudice, however, blinded them to the injustices caused by racial inequality.

The majority of Alabamians opposed women’s suffrage in 1895. They believed politics was the domain of men, and that women had privileged status as wives and mothers and should not involve themselves in political matters. Suffragists adopted an incremental approach to women’s rights and lobbied the Alabama legislature for laws that gave women more control over their bodies and property. In 1900, the Alabama Legislature passed laws that allowed women to will their estate to whomever they wished and have a bank account in their own name. The Legislature also raised the age of consent for women, or girls, from 10 to 14 years of age, a bill they had refused to approve in previous sessions.

Interest in women’s suffrage lagged until around 1912, when success at the national level energized Alabama’s local suffrage groups. HESA reconvened and members faced an immediate challenge finding a regular meeting place. Members hoped to meet at the Greene Street YMCA, as HESA members regularly donated to the YMCA. The YMCA denied their request, stating that women’s suffrage was too controversial. Ellelee Humes, HESA vice president, volunteered her McClung Avenue house for meetings.

Under Humes’ leadership, HESA grew their support and established new suffrage organizations in the Tennessee Valley. By 1915, there were 46 suffrage organizations in Alabama with over 5,000 active members.

Alice Boarman Baldridge, the first female elected to public office in Madison County and the first practicing attorney, and her daughter Vera.

Coordinated lobbying by suffragists led Alabama lawmakers to pass a bill in 1915 allowing women to run for county school board seats. The following year, 10 Alabama women announced their candidacy. Six won, including Huntsville resident Alice Boarman Baldridge who won a seat on the Madison County School board – four years before women had the right to vote. Two years later, at the age of 44, Baldridge passed the Alabama Bar Exam and became Madison County’s first female practicing attorney.

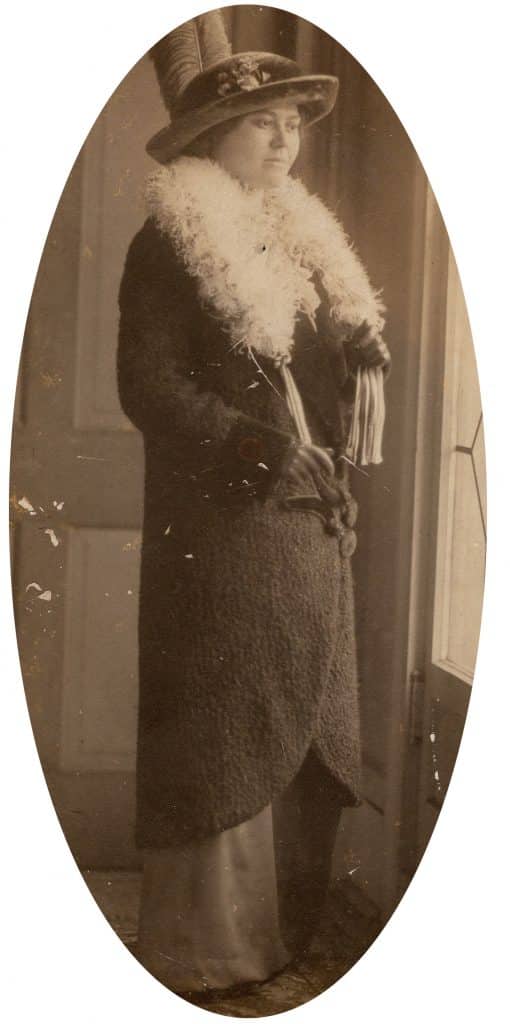

India Herndon, one of six Black Madison County women who voted in 1920. Photo from the Dr. Herndon Spillman collection.

After the ratification of the 19th Amendment in August 1920, Alabama officials began registering qualified women to vote for the upcoming 1920 presidential election. Within two months, 123,000 Alabama women registered, including 1,383 from Madison County, of whom six were Black. Fewer than 200 Black women qualified to register in Alabama.

In the same way that Alabama’s 1901 state constitution denied voting rights to Black men through property, literacy, and residency requirements, the constitution also kept most Black women from the polls in 1920. County officials determined whether a potential voter met registration requirements. The six Black Madison County women who registered in 1920 were affluent, educated, and married to influential men held in high esteem by the white community.

Mary Wood Binford, Ellen Scruggs Brandon, India Leslie Herndon, Lou Bertha Johnson, Dora Fackler Lowery, and Celia Horton Love were the daughters and granddaughters of formerly enslaved people who had established a foothold of success in the decades following slavery. Henry C. Binford, Sr., the father-in-law of Mary Binford, and Daniel Brandon, the husband of Ellen Brandon, held elected office before most Blacks were stripped of voting rights in 1901.

The women and their husbands were active members of Huntsville’s Black business community. Ellen and Daniel Brandon owned a successful construction company. Lou Bertha and Shelby Johnson owned Grand Shine Parlor, a dry-cleaning business. India and A. J. Herndon owned Citizens Drug Store, and Dora and Leroy Lowery owned businesses in the Church Street business district. Leroy Lowery also served on the Board of the Supreme Life Insurance Company of Illinois.

Celia Love was the only woman whose income was related to agriculture. She owned a large farm in Mullen’s Flat, now the site of Redstone Arsenal. Her husband, Adolphus Love, was reputed to be the wealthiest Black man in Madison County.

All of the women had formal educations. Binford, Brandon, Herndon, and Lowery taught at the school eventually named for William Hooper Councill. Mary Binford and her husband, Henry C. Binford, Jr. both graduated from Howard University. Henry Binford retired as the principal of Councill High in 1918.

Like their white counterparts, the Black women were philanthropic and served their community. They were wives, mothers, educators, and business owners. All were members of Lakeside Methodist Church, a hub of spiritual, cultural, and educational activities in the Black community. The first city-supported school for Blacks began in Lakeside’s basement. Black women wanted to vote for the same reasons as white women, but they also knew that voting rights would help secure the safety of their families.

In the decades following the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the votes of Black and white Alabama women helped establish Alabama’s Child Welfare Department, increase appropriations to the Public Health Department, increase the education budget, end the convict labor lease system, and elect the first woman to the Alabama Legislature in 1922.

It was not until 1965 and the passage of the Voting Rights Act that all Alabama men and women gained the right to vote. Huntsville native Rev. Joseph Lowery, a founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and son of Dora Lowery, guided this effort.

Soon, our city will have four new historic markers recognizing the places where Huntsville women made suffrage history. In honor of HESA, a marker will be placed at the Greene Street YMCA and at the former home of Ellelee Humes on McClung Avenue. To honor the six Black women voters, a marker will be placed at Councill High Memorial Park. A marker will also be placed at the former Adams Street home of Alice Baldridge.

Integrating the stories of Huntsville women into our public history through historic markers enhances Huntsville’s reputation of distinctiveness. Huntsville is strong enough to tell the difficult chapters of our history with honesty and empathy, so we can celebrate the progress we have made together.

Mary Binford, second standing from left on back row, with her graduating class at Howard University, 1897. Photo from the Ben Carter collection.

Contributed by Donna Castellano

Donna Castellano is the Executive Director of the Historic Huntsville Foundation, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the preservation of Huntsville/Madison County’s historic resources. Learn more about their community-based mission and projects on their website: historichuntsville.org

This article appears in the October 2020 issue of Initiatives magazine, a publication of the Huntsville/Madison County Chamber.